An engineer’s guide to modern lab control¶

Author: Thomas Ferreira de Lima (tlima@princeton.edu)

Introduction¶

Over the years, software engineering has evolved into a very prominent field that penetrates all industrial sectors. Its core principles and philosophy was to make life easier for consumers to achieve their goals. That was when Apple and Microsoft were created. Then, as the field evolved, it has become important to make software engineering as inclusive as possible to new “developers”, and to make collaboration as seamless as possible. This is the age of the apps. Now, software programming is becoming considered as fundamental as math and science, and are starting to enter school curricula.

Meanwhile, in academic circles and other engineering industries have lagged in software sophistication. Here, I propose a few techniques that we can borrow from software engineering to make our collaborative work in the lab more productive. My inspiration draws from the fact that in software engineering teams, the source code describes the entirety of a product. And if it is well documented, a new member of the team can learn and understand how it works in high or low level without the need for person-to-person training. In other words, all knowledge is documented in source code, instead of a mind hive. This is not the case in research groups. When a PhD student leaves, all his or her know-how suddenly exits the lab.

The concepts¶

Software programming¶

The first tool that is instrumental to this method is software programming. Computers were created with the intention to automate or facilitate menial tasks. The tendency is to delegate more and more of our labor to the machine, so we can move on to the bigger picture.

In our lab, a scientific experiment depends on controlling many instruments at the same time. The more complex the experiment, as they ten to be with integrated circuits, the more instruments are needed and the more complicated the calibration procedures and execution algorithms are. Most of these instruments are designed to have an electronic interface compatible with computers. These can be chiefly USB, which stands for Universal Serial Bus, or GPIB, for General Purpose Interface Bus, or Ethernet. Through these ports, computers can launch commands and probe results at the speed that the interface supports. As a result, one can control instrumentation of an experiment via the computer, i.e. via software. This is called a cyber-physical system. But this is not all. Software can also be used to perform any kind of algorithm. Which means that in a cyber-physical host, an experiment can be defined entirely by a computer program.

Computers programs can be written in a programming language, such as Python, MATLAB, C, Fortran, Java etc. There are many, but they all have the same purpose: to translate english words into machine code. Over a century of math, engineering, logic, and language science has passed since Ada Lovelace wrote the first algorithm intended for a machine. Python is a very modern language, still in active development, that became ubiquitous in the software engineering world due to its flexibility. It is considered a high-level language, meaning that its representation is very close to plain English, while its machine inner-workings are very hidden insides. Normally, these programming languages result in programs that are slower than the ones written in a more low-level language. Python’s popularity stems from the fact that it can directly interface with a lot of these other faster languages, and it is fast enough for most people with modern computers. It also offers myriad open-source libraries that offer everything from web apps to numerical simulation to deep learning. So Python nowadays is the favorite first language of scientists, engineers, developers, students etc.

Version control¶

It is possible to use a particular programming language to write routines and small scripts that can have inputs, crunch some numbers, and produce outputs. However, actual programming languages were created to support Turing complete applications, which support an infinite complexity of internal states and behaviors. When source code became too complicated, i.e. around the time of the Apollo missions, computer scientists invented object-oriented programming, which made possible the modularization of source codes. This meant that programmers could change a piece of the code that interacted with the entire application without necessarily having to fully understand the entire source code. As a result, programmers needed a central location to store the code so they could edit it at the same time. This was called version control. Version control has become standard in all industries that deal with software. It is so efficient that it allows thousands of programmers to collaborate on an opensource project, each one submitting small changes, without risking introducing new bugs.

There are many technical ways to achieve version control, and many different software written to accommodate these techniques. The most popular are Git, Subversion, Mercurial and Microsoft’s Team Foundation Server. Like it or not, today, Git dominates the version control software arena, and is rendering the others rather obsolete. So let’s talk about version control as designed by Git’s developers.

Version control with Git¶

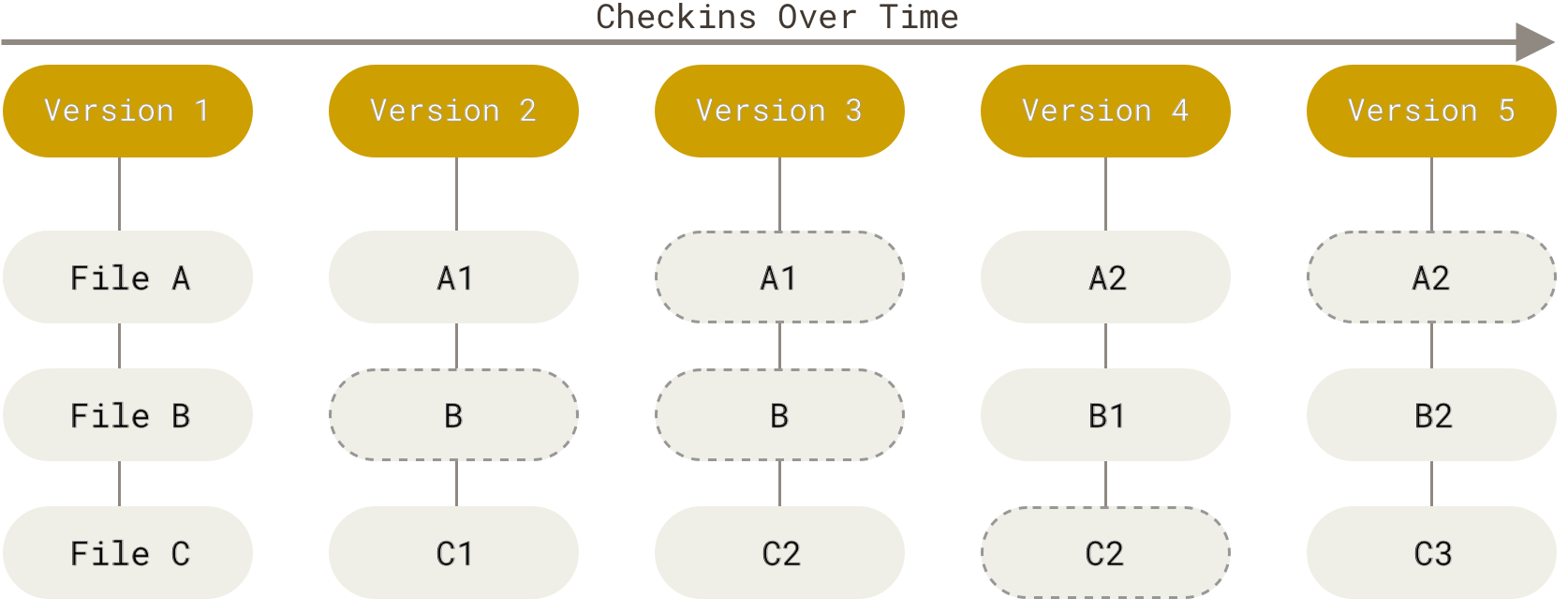

The most basic concept of version control is revision tracking. Every revision to the source code is recorded by a “commit”. The commit records the changes made by the user respective to the previous revision. You can think of it as a linear graph, where the nodes represent the different revisions of the entire source code and the arrows the history connecting them. This is useful because the history of any project is automatically recorded and documented. Teams also use this feature to track how active their developers are.

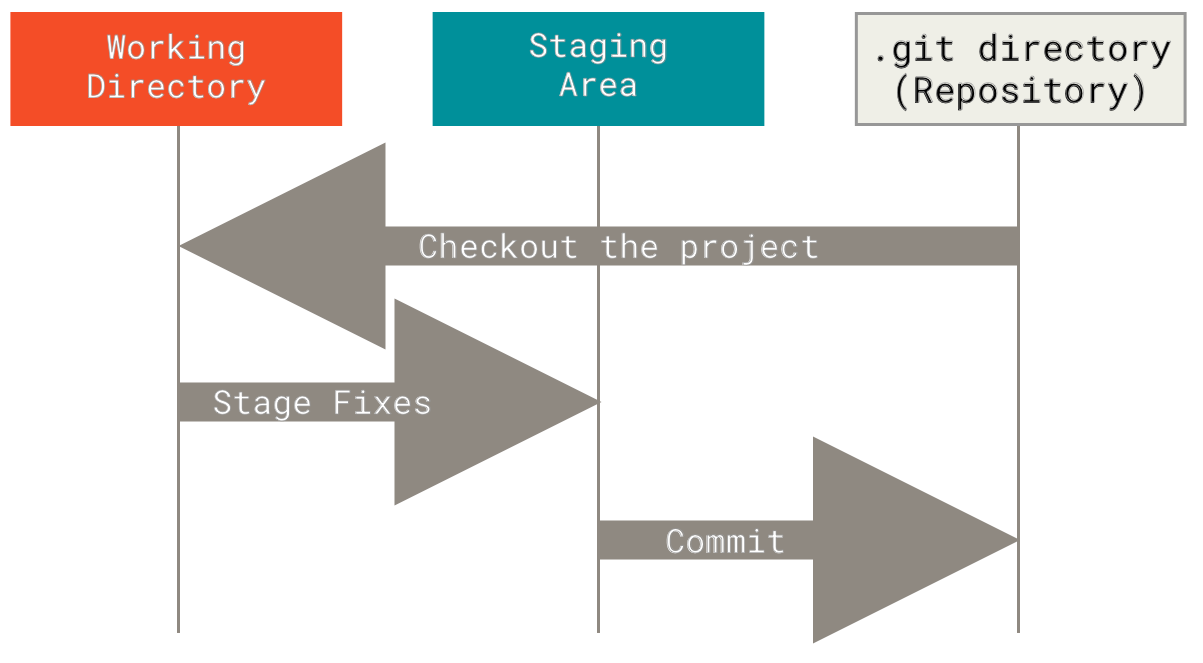

Commits are created and stored in what is called a repository, which is a data structure that keeps track of all commits made in history. In Git, this repository is stored in your computer, so that you can interact with it offline. The process typically works as follows. You work on the documents and code normally with your favorite editor, changing them on disk. When you have finished a desired set of changes, you create a commit and document what you have included in that particular commit, so that future you or collaborators have a sense of what changes were made before looking into the code. When a commit is triggered, the software automatically detects the changes that were made to every file, including whether it was deleted, renamed, or whether its metadata was changed. It then creates a manifest of all these changes, compresses it, and generate what is then called a “commit”. After that, the commit is automatically stored in your “local repository”, which is hidden inside a folder named “.git”.

git commit -m “message”

There are two concepts which, at this point, confuses most people unfamiliar with version control: staging and remote vs. local. But they are not complicated at all. The concept of staging can be understood by the following example. Say that there is a project/repository with two main parts: a numerical simulation part, and an experimental data processing part. Their code is contained in different files. You have made changes to both of these files because you are working on them at the same time, but you have finished implementing a desired change in the simulation file, but the one on experimental data is still in progress. Therefore, if you want to commit the changes you have made on the simulations while ignoring the rest, a staging step is necessary prior to commit. You add the simulation file to what is called a stage, leaving the experimental processing out of the stage. This allows you to commit only what is on the stage.

# Edit simulation file

git add simulation.py

git commit -m “finished simulation”

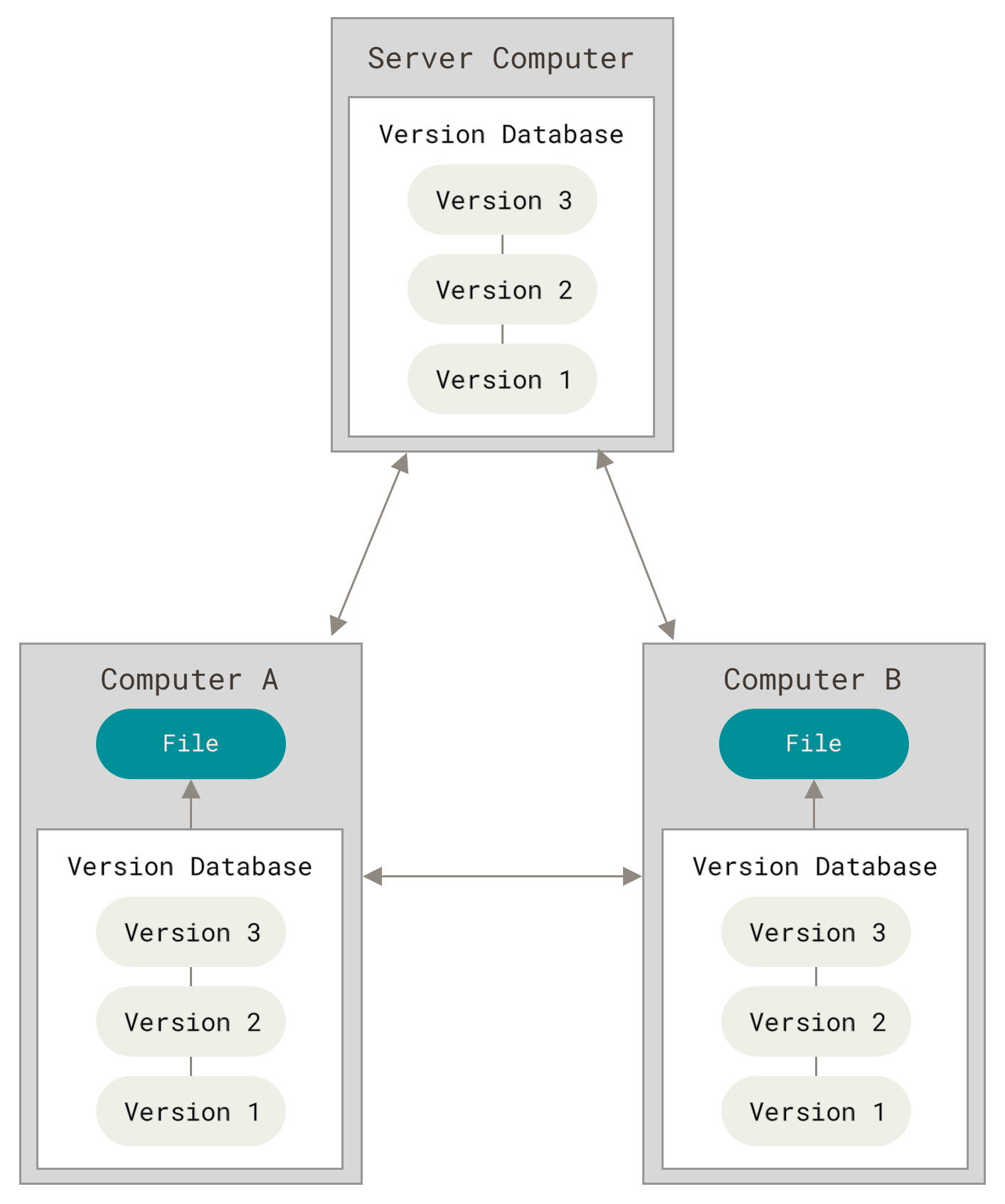

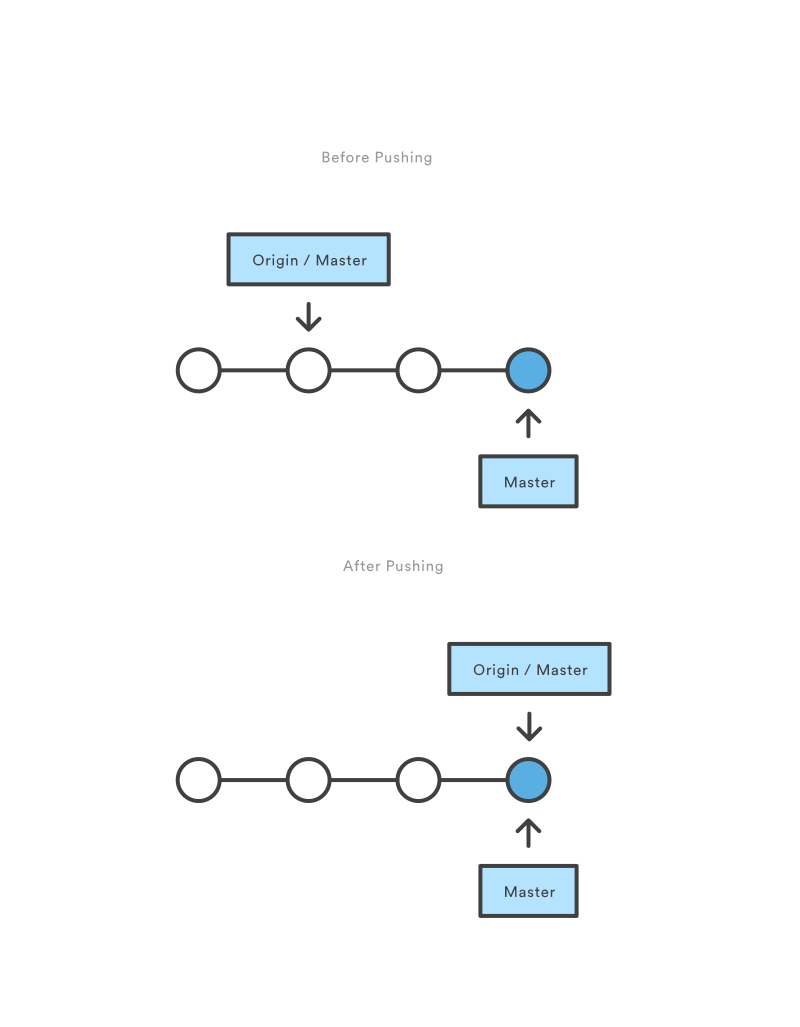

Another interesting property of Git is its ability to separate remote and local copies of the repository. In order to make the source code available to others, it needs to be uploaded somewhere remote. That is the raison d’être of a remote repository. There are web services that can host remote repositories, most famously GitHub, where virtually all the opensource projects are stored nowadays. The local copy of the repository is an exact and entire copy of the remote one, that is why one must “clone” it to the local computer. Clone, in this case, means download the current version plus all other versions in history. Therefore, after a commit is created in the local repository, it must be “pushed” to the remote copy so others can see it and “pull” to their local copy.

# Edit simulation file

git add simulation.py

git commit -m “finished simulation”

git push

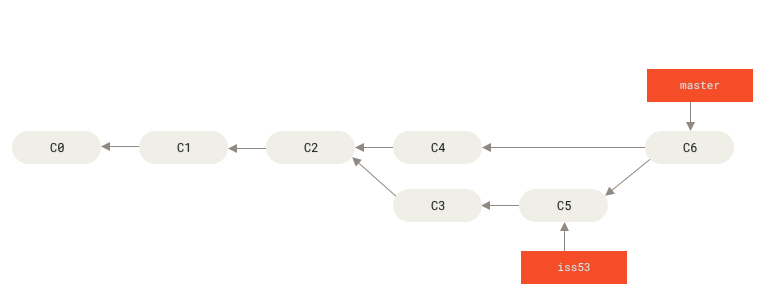

The other main property of Git is that it can automatically “merge” a number of edits together in one step. Its algorithm is very powerful, works flawlessly when it can, and falls back to human intervention in case of “conflicts”. When two collaborators create local commits, their history tree forks into two parallel versions that need to be conciliated. If one pushes first, the other’s push will fail and abort, because its local repository does not agree with the most recent state of the remote repository. So the proper procedure is to sync the local with the remote by “pulling” changes from remote:

# Edit simulation file

git add simulation.py

git commit -m “finished simulation”

git pull # this is where the merge happens

git push

The merge algorithm works in the following way. It attempts to add all modifications from both revisions to a stage. First, if the modified files are different, then both files are simply added to the stage. If the same file is modified, then Git will start a “diff” operation. It will go through line by line on each revision of the file until it detects a discrepancy. The revisions considered are the baseline (the revision agreed upon prior to the commit), the remote, and the local. Each discrepancy is judged as addition, deletion or simply edits. If Git detects a discrepancy both in the remote and the local commits, then a conflict is triggered, and the user must resolve it themselves by choosing to maintain changes from one revision or the other, or altering the line altogether. After the merge operation is finished, all files are added to the stage and a new commit is created. This commit is special because it has two “parents”, so the history graph will look like three branches which merged together. Note that this process is designed such that no changes are lost during merge. It is an automatic way of doing a very tedious task that humans used to do in the past.

Here is a tutorial on Git.

Servers, hosts and clients¶

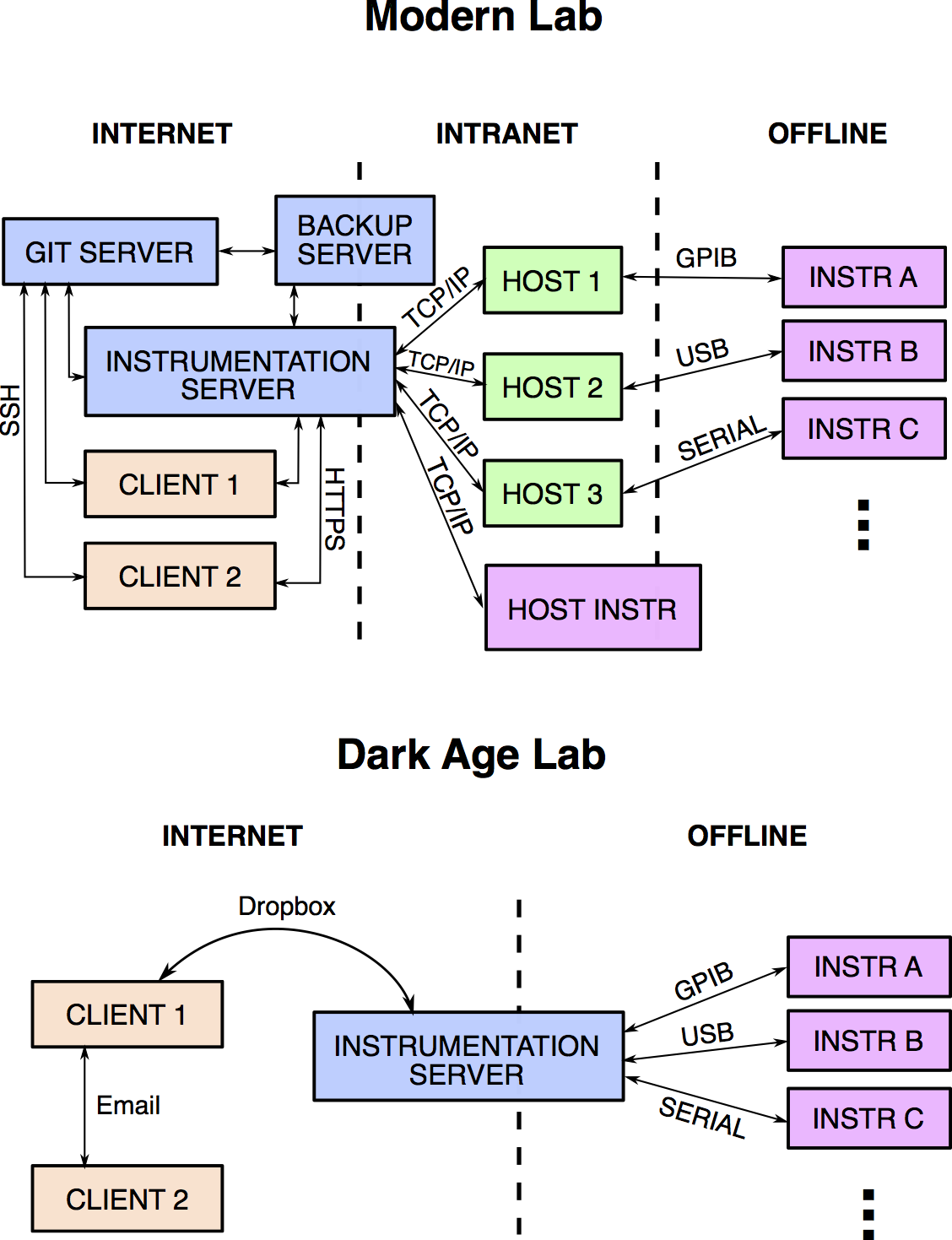

In order to make this all work, we need servers, hosts, and clients. A computer server can refer to the software or the device used in the “client—server” model. So you can have many software servers running on different server machines. As you can see, it can get complicated really fast. So unless otherwise specified, let us understand the word server as powerful computers that are expected to be turned on and connected to the network at all times.

A host is any computer (or device) connected to the network. So all servers are hosts, but not all hosts are servers. If one wants to be able to control a certain instrument via the network, this instrument should either be a host itself or be connected to one via some interface bus. There are so many ways to do this that it would be counterproductive to introduce them all. But it is important to understand why these hosts cannot be servers. Simply, when you connect a new instrument to the host, sometimes one must install new software, update software drivers, or even reboot the machine. Stuff that cannot be allowed on a server that serves multiple clients at the same time.

Finally, a client is a workstation that depends on resources offered by the server. It can be our personal computers.

In most research laboratories that require some sort of automation, researchers typically use one single computer to directly connect to the instruments that execute the experiment. A scientist can do this, download the data to her personal computer, go home, and crunch the numbers. This has been a good enough practice for simple experiments where there was a single person dealing with the instrumentation and the data analysis. However, when multiple persons need to have access to the most recent data, or even access to the experiment, it makes more sense to have a client—server—host implementation. In software engineering, the source code of some large projects such as Facebook grew to hundreds of gigabytes, with compilation times up to days. For them, having the source code stored and compiled on a supercomputer server is crucial.

The tools¶

In the following sections, I describe the tools that we need to be used to accommodate a team of two or more researchers operating various experiments in lab with multiple instruments connected to different hosts. Based on the the concepts described above, we need a central Git repository server, a server that connects to all hosts and a program that controls instruments and collects data from the hosts.

The Git server¶

As previously mentioned, the Git repository is a set of files that can be stored anywhere. There are services online that offer free storage for opensource projects or paid storage for closed source projects. The most famous one is github.com. It is also possible to install a Git (software) server on a local server for free, so long as you possess the hardware. Gitlab, for example, has the same functionality of Github and it is also easy to use and install. It allows the admins to control which users have access to which repositories, which can be useful to protect confidential data. And since Git repositories are the same everywhere, they can be exported to other services very easily.

The instrumentation server¶

Another server has to be created and loaded with drivers from the instrument vendors, and also loaded with software modules that will support connecting to the hosts. This server can be created in the same machine as the Git one, but it is a good idea to separate them, because Git has to be extremely available at all times to everyone so that collaboration does not stop. It is quite a disturbance when Git goes offline, even if once a month, whereas the instrumentation server could go offline routinely for maintenance.

Software programming with Python notebooks¶

Python is a dynamic programming language, which in computer science means that it can be executed line by line instead of compiled into machine code. Because of this, Python can be used as a scripting language, like MATLAB, as well as a full-fledged object-oriented programming language, like C++. This flexibility means that one can build computer programs that are installed into the operational system of the computer, which can be accessed by Python scripts in the same computer or in another computer in the network. These programs, in Python language, are called packages. Other languages call them libraries, but essentially it means the same thing.

A Jupyter notebook is an “opensource web application that allows you to create and share documents that contain live code, equations, visualizations and narrative text.” It is a kind of document that exists “live” in a server, like Google Doc. It is interactive and can be shared with other users. Here is a list of interesting jupyter notebooks. It can be used to plot data beautifully, write LaTeX annotations, and store logic and results in the same file! If this notebook application is installed in the instrumentation server, one gains the ability to interactively control experiments, collect data, analyze it, and plot publication-quality figures on the same notebook. This workflow, combined with the possibility of “versioning” the notebooks in a Git repository, is a superior way of making sure the experiments are reproducible, well documented, and self-explanatory to anyone in the lab who wants to start afresh.

The lightlab package¶

The lightlab Python package is being developed in the Lightwave Lab to be essentially our own version of LabVIEW + MATLAB. The opensource community built enough libraries for Python that would render these two software obsolete. While many companies still release drivers and plugins for LabVIEW and MATLAB, they are also easy to interface with opensource libraries. As of 2017, we can essentially control every remote-controlled instrument with the lightlab package.

The lightlab package contains three things: instrument drivers, laboratory virtualization, and calibration models for photonic devices. (It has been decided to remove the calibration models from the project, and give it its own package, so I will not explore it here).

Instrument drivers¶

Instrument drivers are pieces of code responsible to command and control instruments. For example, a Keithley 2400 source meter can be controlled via GPIB protocol. National Instruments offers a set of low-level drivers (NI-VISA) that can be installed in Linux or Windows hosts, which allows us to establish connection, send and receive GPIB (or, more modernly, VISA) commands easily. These are files that have to be installed directly into the operational system. Then, we can install an opensource package called PyVISA, written in Python, which interfaces with the low-level NI-VISA drivers. The lightlab package contains an object built onto PyVISA, representing the Keithley 2400 instrument. This object contains functions that can translate commands such as turn on, turn off, ramp up current or voltage, read resistance, voltage or current values; into VISA commands that can be sent through the NI-VISA drivers. This object can be accessed directly from the Jupyter notebook.

Laboratory virtualization (under development)¶

Another thing present in the lightlab package is the virtualization of instruments. The idea is very well suited for automated testing and data collection of devices. In this module, every object that we interact with in lab will have a corresponding Python object. An instrument is an object that understand where the instrument is located in lab, where it is connected to, and via what host it can be accessed to. Similarly, a device object contains a map of different ports it can be connected to. This way, users can design the experiment entirely on the computer with a Python notebook, simulate the expected behavior, and using the same code, perform the experiment in real life. This creates the idea of a “source code “ of the experiment, which can be executed by future users or users in different labs with different instruments.